May 2024

May 2024

“Never Again” Yad (Torah Pointer)

Marjorie Simon (b. 1945)

Mild steel, sterling silver, 18k gold, brass, copper, model train railroad track, carborundum grains, vitreous enamel, carnelian

2021

Collection of Barr Foundation Judaica

In honor of both Jewish American Heritage Month and Yom HaShoah, also known as Holocaust Remembrance Day, we are featuring one of the yads that can currently be seen at the Skirball Museum in our new exhibition, The Guiding Hand: The Barr Foundation Collection of Torah Pointers.

Marjorie Simon’s “Never Again” yad distills a horrific chapter of the Jewish past and the hope for a Jewish future, all in one remarkable piece. The yad, which is a Torah pointer meant to help someone keep their place as they read from a Torah scroll, has distinct designs on either side. On one is the phrase that was displayed over the gate to the concentration camp Auschwitz—arbeit macht frei, work sets you free. A miniature cattle car sits atop the yad, recalling the countless Jews who were forced into cattle cars and sent to concentration camps across Europe. On the other side, the same cattle car is burnished with age, appearing more like a historical relic. A golden and green pair of vines climbs up the yad, evoking new hopes and growth for the Jewish people.

This yad, and other similarly beautiful and creative ones, is currently on display in The Guiding Hand exhibition. Artist Marjorie Simon is a Jewish American jeweler, enamellist, writer, and teacher.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

“Never Again” Yad (Torah Pointer)

Marjorie Simon (b. 1945)

Mild steel, sterling silver, 18k gold, brass, copper, model train railroad track, carborundum grains, vitreous enamel, carnelian

2021

Collection of Barr Foundation Judaica

April 2024

April 2024

Matzah Cover

Linen, Embroidery, crochet lace

Late 19th century, Austro-Hungarian

14 13/16 x 18”

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

This April, we look forward to the holiday of Passover, and we will be featuring various Passover-related Judaica. Passover is a spring holiday for the Jewish people when families and communities gather to celebrate the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in Egypt to freedom. Various foods eaten throughout the meal are representative of aspects of this ancient story, and as a result, various pieces of art have been created to hold these foods, such as special cups and plates. But for our Object of the Month, we are kicking things off with something a little different.

This matzah cover is a spectacularly well-preserved piece of textile culture from the 1800s, and it showcases women’s contributions to beautifying the Passover table. The artist—possibly the ‘Muki Terėz’ whose name is embroidered at the top of the cloth—has used cross-stitch to create a beautiful design in rich scarlet and bright blue. The cloth is covered in detailed floral and geometric patterns, and it would have been used to cover matzah, the Passover flatbread, during the meal.

Most striking about the piece is the Hebrew embroidered around it. In blue, we have the words ‘matzah,’ ‘Pesach’ (Passover), and ‘maror’ (bitter herbs), referencing both the Hebrew name of the holiday and its two major symbolic foods. The center text in red reads ‘Hallelujah!’ Starting from the right and reading counter-clockwise, the red text reads, ‘B’chol dor vador, chayav adam lirot et-atzmo k’ilu hu yatza miMitzrayim’—in each and every generation, a person is obligated to see oneself as if one left Egypt. This is one of the main ideas of Passover—that each Jewish person relives the ancient story as if it happened to them personally. It allows for connection between the generations, going back to the time of the Exodus.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

Matzah Cover

Linen, Embroidery, crochet lace

Late 19th century, Austro-Hungarian

14 13/16 x 18”

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

March 2024

March 2024

Ancient Scroll

Moshe Castel (1909-1991)

Safed, 1940s

Enamel on paper

Gift of Polly and Jacob Stein in memory of Edith and James L. Magrish

In honor of the forthcoming holiday of Purim, our March Object of the Month is Ancient Scroll, a piece by Moshe Castel that depicts a scene from the Biblical book of Esther. Drawn from chapter 6 of Esther, the figures are Haman and Mordechai. Haman, the Persian king’s wicked advisor, reluctantly leads his enemy, Mordechai, on horseback through the streets of Shushan as a reward for saving the king’s life. Mordechai is dressed in the king’s very own robes to honor his deed, while Haman is identifiable through his famous triangular hat. On Purim, cookies called hamantaschen are baked to look like Haman’s hat.

Born in Jerusalem in 1909 to a Sephardic Jewish family, Castel was highly influenced by the art of Picasso, Miro, and Gauguin. He made his artistic home in the city of Safed, where he helped to establish the New Horizons group. Much of his art focused on joining the worlds of European art to ancient Near Eastern motifs.

This particular piece is part of Castel’s series completed in the 1940s, which concerned Biblical subjects in Surrealist and Cubist styles. Many of his works include symbols and signs from ancient Hebrew, Canaanite, and Sumerian culture. He also enjoyed employing unlikely materials in his art, such as ground basalt molded into shapes.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

Ancient Scroll

Moshe Castel (1909-1991)

Safed, 1940s

Enamel on paper

Gift of Polly and Jacob Stein in memory of Edith and James L. Magrish

February 2024

February 2024

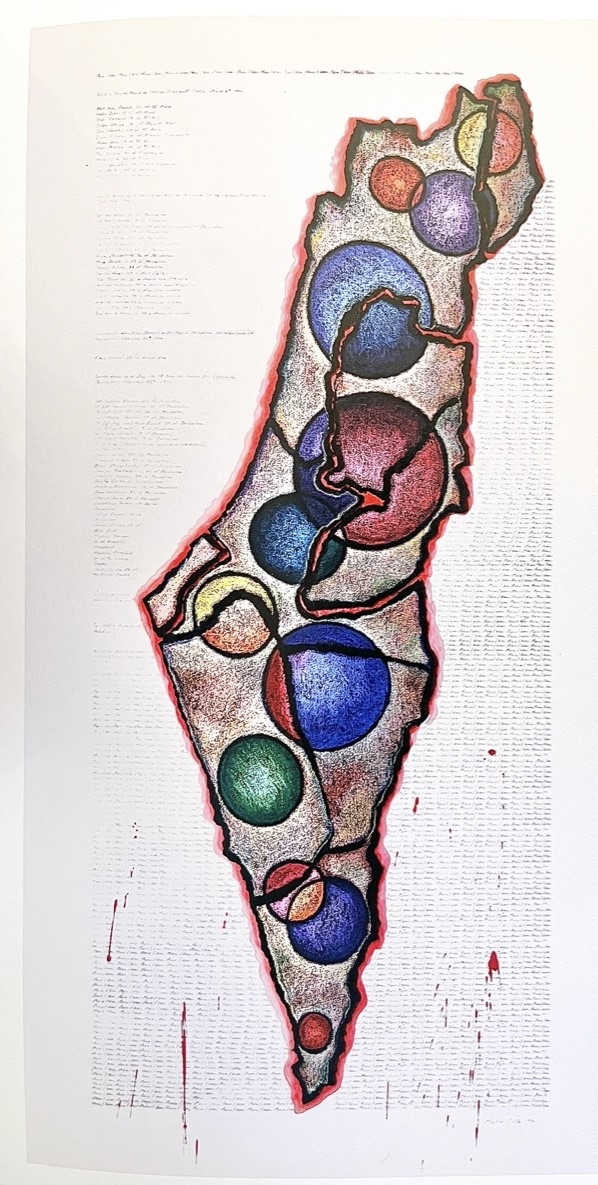

Peace/War

Marlene Siff (b. 1936)

Mixed media including watercolor and oil pastel on torn paper, 84 x 42 in.

Westport, Connecticut

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection, gift of the artist

For our February Object of the Month, we selected a piece that speaks to the ongoing conflict in the Middle East and to how the shockwaves of violence reverberate outward from their origin. This mixed media piece, entitled Peace/War, is by Marlene Siff. An American artist, Siff has had her work exhibited in places like the U.S. Capitol Building, the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum, and Galerie Musée in Nagoya, Japan.

Siff dedicated this piece “in memory of innocent victims whose lives were extinguished by senseless acts of violence.” In the background, names of victims of terrorist bombings are listed in pale writing on either side of a map of Israel on which brightly colored circles cover major population centers where terrorist attacks have occurred. The colors overlap and bloom with the sense that the color will expand and the violence will spread. Even the red outline devolves into splatters at the bottom of the piece that evoke blood.

Ori Soltes, the former director and curator of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum, wrote of the piece, “Although it focuses on Israel, it pertains really to all of human geography and all of human history, raising questions that don’t necessarily have answers.”

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

Peace/War

Marlene Siff (b. 1936)

Mixed media including watercolor and oil pastel on torn paper, 84 x 42 in.

Westport, Connecticut

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection, gift of the artist

January 2024

January 2024

JuChriLam

Wolfgang Ritschel (1933-2010)

Lithograph, signed lower right, undated

Skirball Museum; gift of James Grizzle

As the new year begins, we set our intentions for what we hope will be a peaceful and fulfilling 2024. Our object of the month reflects these intentions as we pray for peace in Israel. This lithograph, entitled JuChriLam, is named for the three Abrahamic religions whose origins are tied to Jerusalem: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The piece reflects how these three religions make up the fabric of spiritual life in Jerusalem, featuring religious symbols, places or worship, and worshippers from all three faiths. The central image depicts one of the famous Marc Chagall windows, The Tribe of Dan, from the Hadassah Hospital.

The artist, Wolfgang Ritschel, was born in Trautenau but raised in Vienna, Austria, where he attended the university and earned four degrees in various medical fields. Ritschel traveled the world as a teacher before settling down in Cincinnati in 1968 and teaching pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics at the University of Cincinnati. While he taught, he took classes in painting and sculpture. As he developed his talents, he began to exhibit his work and had over 60 solo shows in the course of his career, spanning decades and continents.

Ever the world traveler, Ritschel often painted cities and landscapes from the places he visited. He described his painting style as ‘expressionism influenced by fauvism.’ JuChriLam shows Jerusalem not only as it is, but as it could be at its very best: a whirl of color, energy, and intimacy between the world religions that call it home. Nuns, priests, rabbis, and imams swarm the painting, one on top of the other, in what almost evokes a family portrait.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

JuChriLam

Wolfgang Ritschel (1933-2010)

Lithograph, signed lower right, undated

Skirball Museum; gift of James Grizzle

December 2023

December 2023

Hanukkiyah (Hanukkah Lamp)

British Mandate Palestine, 1910

Brass

Gift of Sally and Gerry Korkin, John and Lisa Fox, and Marguerite Kiefer

In memory of Dr. William Rosenau

December is here, and this year, the holiday of Hanukkah falls from the 7th through the 15th of December. Jewish families gather for eight nights to commemorate the miracle of the Maccabees. After fighting Seleucid Greek occupation in Jerusalem, the rebel Maccabees were able to reclaim the city and rededicate the defiled Temple. The story goes that there was not enough oil to light the lamp, or menorah, in the Temple and eight days would be needed to make new oil—yet the small amount sustained the menorah until the new oil was ready. To commemorate this event, we eat foods cooked in oil, like latkes and donuts called sufganiyot, and we light one candle for each of the eight nights the oil lasted.

The centerpiece of the holiday is a hanukkiyah, which is a special kind of menorah, with nine candles. Eight of these represent the eight nights of Hanukkah, while the ninth central candle is called the shamash, or helper, is used to light the others. This particular hanukkiyah, made in British Mandate Palestine by an unknown artist, was likely made by someone who had escaped the rise in antisemitism in Europe at the turn of the century. The metal makers of this era used the same visual language of their European modern counterparts, so this hanukkiyah is a classic—eight candles equally spaced out, with the shamash slightly elevated, and featuring a Star of David in the middle.

This hanukkiyah was gifted to the Skirball museum in memory of Dr. William Rosenau, who brought this beautiful piece from British Mandate Palestine to the United States. A graduate of Hebrew Union College, one of the windows in the Scheuer Chapel is dedicated in his memory. Like many graduates of the college, Rosenau was a pioneer of Reform Judaism and succeeded in introducing Friday night Shabbat services and English prayers at his Baltimore synagogue, Congregation Oheb Shalom. Rosenau was also very active in Jewish organizations and charities, such as the Jewish Welfare Board and Associated Jewish Charities.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

Hanukkiyah (Hanukkah Lamp)

British Mandate Palestine, 1910

Brass

Gift of Sally and Gerry Korkin, John and Lisa Fox, and Marguerite Kiefer

In memory of Dr. William Rosenau

November 2023

November 2023

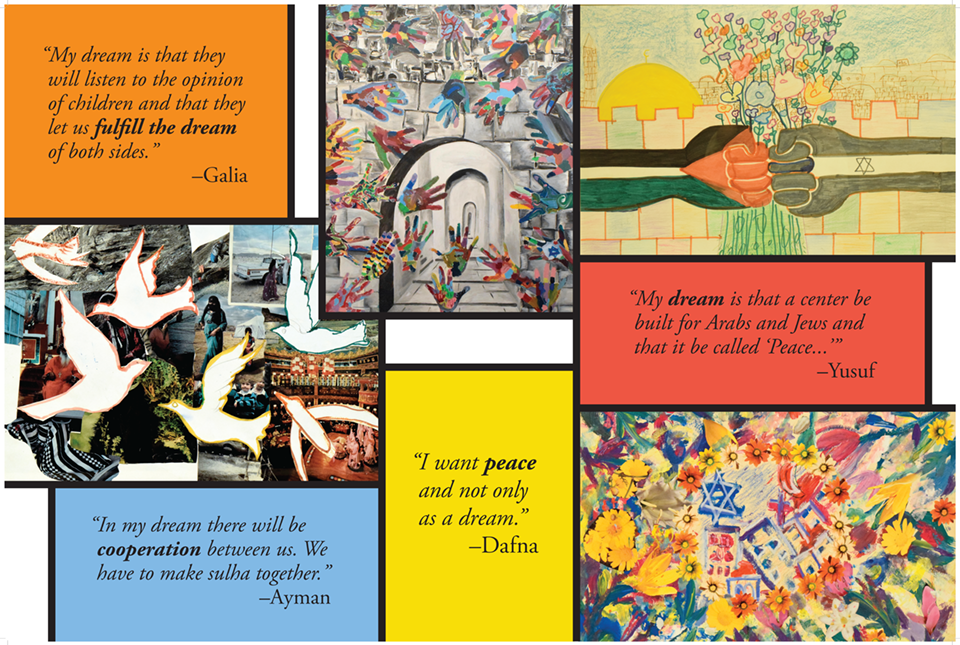

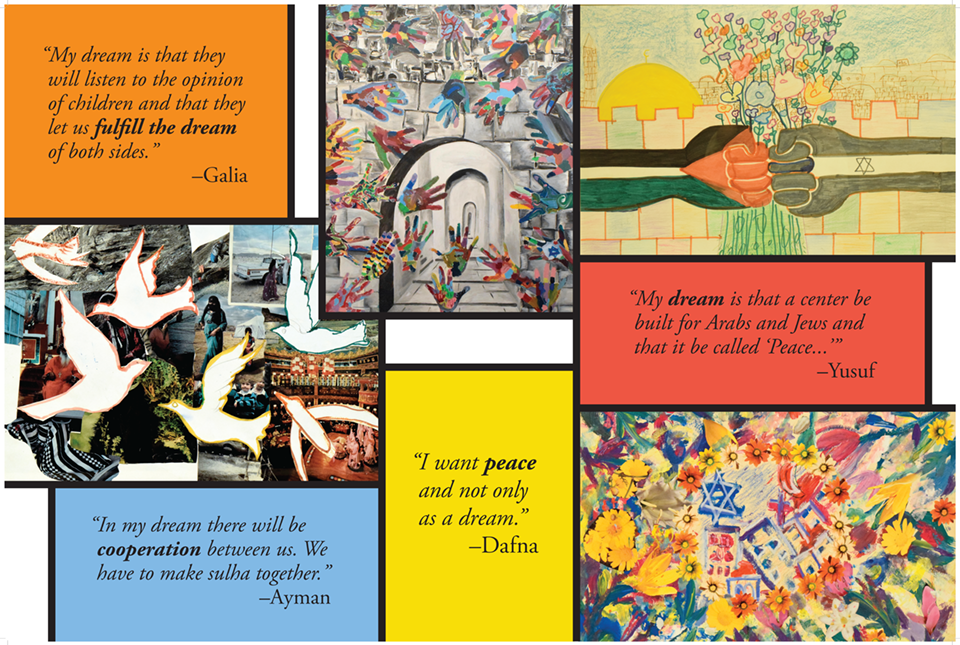

Painting Pain Dreaming Peace

Israel, 2000-2003, 2007-2010

Mixed media

Gift of the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities

In the wake of the attack upon Israel and declaration of war upon Hamas, the object of the month reflects a similar period in Israel’s recent history and the power of art to connect seemingly opposing sides and find unity in dreams of peace, cooperation, and friendship.

When the second intifada (an armed uprising of Palestinians against Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip) broke out in the fall of 2000, virtually all coexistence programs between East and West Jerusalem came to an abrupt halt. In that same year, a unique program was developed by the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities to bring elementary school children—Arabs and Jews, Palestinians and Israelis—together with art teachers in a setting of mutual understanding and friendly relations. The program was designed to give a voice to the children and to offer them the opportunity to express their emotions.

The name of the resulting collection is “Painting Pain Dreaming Peace.” Of the more than 150 artworks created as a result of this program, four were chosen for this banner. The names of the pieces, clockwise from the top, are “All Our Hands to the Light,” “Friendship,” “Where Religions Flourish,” and “Peace for All.” Interspersed among the drawings, made jointly by Arab and Israeli schoolchildren, are quotes from some of the students about their dreams for the future. This banner was the contribution of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum to the “Under One Roof: Sukkah Art Exhibit” at the JCC this past Sukkot.

This post was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this school year.

Painting Pain Dreaming Peace

Israel, 2000-2003, 2007-2010

Mixed media

Gift of the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities

October 2023

October 2023

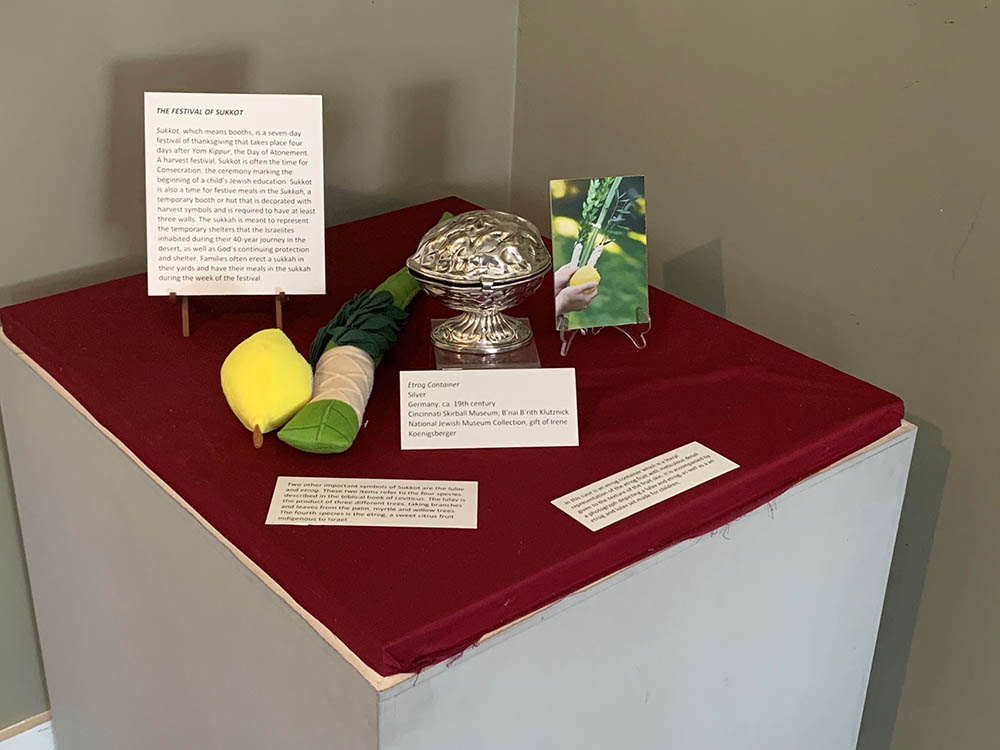

Etrog Container

Zelig Segal

Israel, 1989

Sterling silver and mahogany

Gift of Dr. Stanley and Judy Lucas in honor of their 40th Anniversary

Etrog Container

Germany, 19th century

Silver

The High Holy Days have come and gone, but the season of our joy is far from over. The first of October marks the second day of Sukkot, a weeklong harvest festival for the Jewish people. During the week of Sukkot, we call to mind the Israelites in the desert, whose dwellings could only be temporary as they wandered toward the Promised Land, and we build temporary dwellings of our own, which we call a sukkah. Most sukkot are decorated with plants that evoke harvest time; the sukkah on the lawn that the Skirball Museum shares with Hebrew Union College has a roof of corn stalks, loosely set so those inside the sukkah can peek at the sky as they eat their meals and study beneath it.

Another feature of the holiday of Sukkot is to shake the lulav and etrog. These two items refer to the four species described in the book of Leviticus. The lulav is the product of three different trees, taking branches and leaves from the palm, myrtle, and willow trees. The fourth species is the etrog, a sweet citrus fruit introduced to Judea around 500 BCE.

Our two objects of the month pay homage to the etrog, which is shaken in six directions with the lulav. During the week of Sukkot, the etrog, which is a precious and often expensive commodity, is placed in the etrog holder when not in use. We are featuring two etrog holders for October. The first comes to us from 19th century Germany, wrought in silver and shaped like the fruit it represents. It signifies a traditional approach to Sukkot-related art and ritual objects. By contrast, our second etrog holder is much more abstract. It is an Israeli piece, made in 1989 by Zelig Segal, and a mahogany base holds the silver capsule aloft. The design is simplistic and modern, almost resembling a spaceship. Both etrog holders symbolize the cultural value over time of the etrog fruit, which must be kept safe and intact for the week of Sukkot.

This entry was written by Rachael Houser, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR Cincinnati. She is thrilled to work as an intern on behalf of the Skirball Museum this academic year.

Etrog Container

Zelig Segal

Israel, 1989

Sterling silver and mahogany

Gift of Dr. Stanley and Judy Lucas in honor of their 40th Anniversary

Etrog Container

Germany, 19th century

Silver

September 2023

September 2023

Rosh Hashanah

Arthur Szyk (Poland 1894—1951 Connecticut)

New York, 1948

Lithograph from The Holiday Series: Six Paintings of Jewish Holidays

Cincinnati Skirball Museum

Gift of Anita and Edward G. Marks

The High Holy Days, which begin this year at sundown on September 15, call to mind memories of Rosh Hashanahs and Yom Kippurs of our past—families gathering together to share a festive meal, crowded synagogues, and old stories made new again. This lithograph, entitled Rosh Hashanah, perfectly encapsulates the energy of the High Holy Days, when Jews welcome the new year on Rosh Hashanah, and engage in self-reflection and atonement on Yom Kippur. Men in rich tallitot, or prayer shawls, read along in their prayerbooks as the rabbis lead them through the blessing of the holiday candles. On the top right, a man blows a shofar (ram’s horn) to herald the new year. On the top left, women pray in the balcony.

The artist, Arthur Szyk, evokes Jewish communal life in a way that was all too familiar for him. A self-proclaimed “soldier in art,” Szyk was best known as an activist-artist who utilized caricature and political cartoons to speak out against the rise of the Nazi Party during World War II. He was born in Łódź, Poland and quickly proved himself an adept talent. He was fifteen at the time of his first exhibition, and he studied in Paris before he was conscripted into the Russian Army during World War I. Szyk spent later years in his life in England, France, and the United States. His body of work was immense, consisting not only of satirical-political works of art but watercolors and illuminations.

Judaism and democracy were themes that continued to show up in Szyk’s art and life. He received the George Washington Bicentennial Medal for his exhibitions and worked tirelessly for the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe during the Holocaust. Perhaps his most famous work of art is the Szyk Haggadah, a book of prayers and readings for the festival of Passover.

An interesting feature of Rosh Hashanah sticks out to the eagle-eyed viewer. The Torah scroll in the center is open to the very first verses of Genesis. Since Rosh Hashanah is the ‘birthday of the world,’ this is especially apt. But it appears Szyk might have been making a statement about American Judaism as well. The traditional reading for Rosh Hashanah is Genesis 21 and 22. It is an American Reform Jewish custom to sometimes read from Genesis 1 to honor the ‘birthday of the world.’ Even in the midst of an Orthodox celebration of the new year, a Reform custom has found its way into the picture.

Rosh Hashanah

Arthur Szyk (Poland 1894—1951 Connecticut)

New York, 1948

Lithograph from The Holiday Series: Six Paintings of Jewish Holidays

Cincinnati Skirball Museum

Gift of Anita and Edward G. Marks

August 2023

August 2023

Mizrah

Russia, 1810

Ink and gouache on cut paper 11 ¾ x 15 ¾ in.

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection; gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz

Mizrah is the Hebrew word for “east” and the direction that Jews in the Diaspora west of Israel face during prayer. Practically speaking Jews face the city of Jerusalem when praying, and those people north, east, or south of Jerusalem face south, west, and north respectively. In European and Mediterranean communities west of Israel, the word mizrach also refers to the wall of the synagogue that faces east, where seats are reserved for the rabbi and other dignitaries. In addition, mizrah or mizrach refers to an ornamental wall plaque used to indicate the direction of prayer in a Jewish home.

The symmetrical papercut for the eastern wall shown here is an example of folk art popular in the 19th century. Its arched silhouette is filled with delicate floral motifs and geometric forms—circles, arches, squares, and rhombuses—all cut with great precision. Other motifs include various species of water fowl, caged squirrels, fish, and a pair of lions.

The papercut is inscribed with the word “Mizrah” at the top, and the following words at the bottom: “This papercut was prepared as a gift to a friend by Ephraim Joseph Ginsburg.”

This mizrah recently appeared at Miami University’s Richard and Carole Cocks Art Museum as part of the exhibition Experiencing the Divine: Devotional Practices of Islam, Judaism & Christianity. It will go on view for the first time at the Skirball Museum in the second-floor auditorium gallery of Mayerson Hall later this summer.

Mizrah

Russia, 1810

Ink and gouache on cut paper 11 ¾ x 15 ¾ in.

B’nai B’rith Klutznick Collection; gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz

July 2023

July 2023

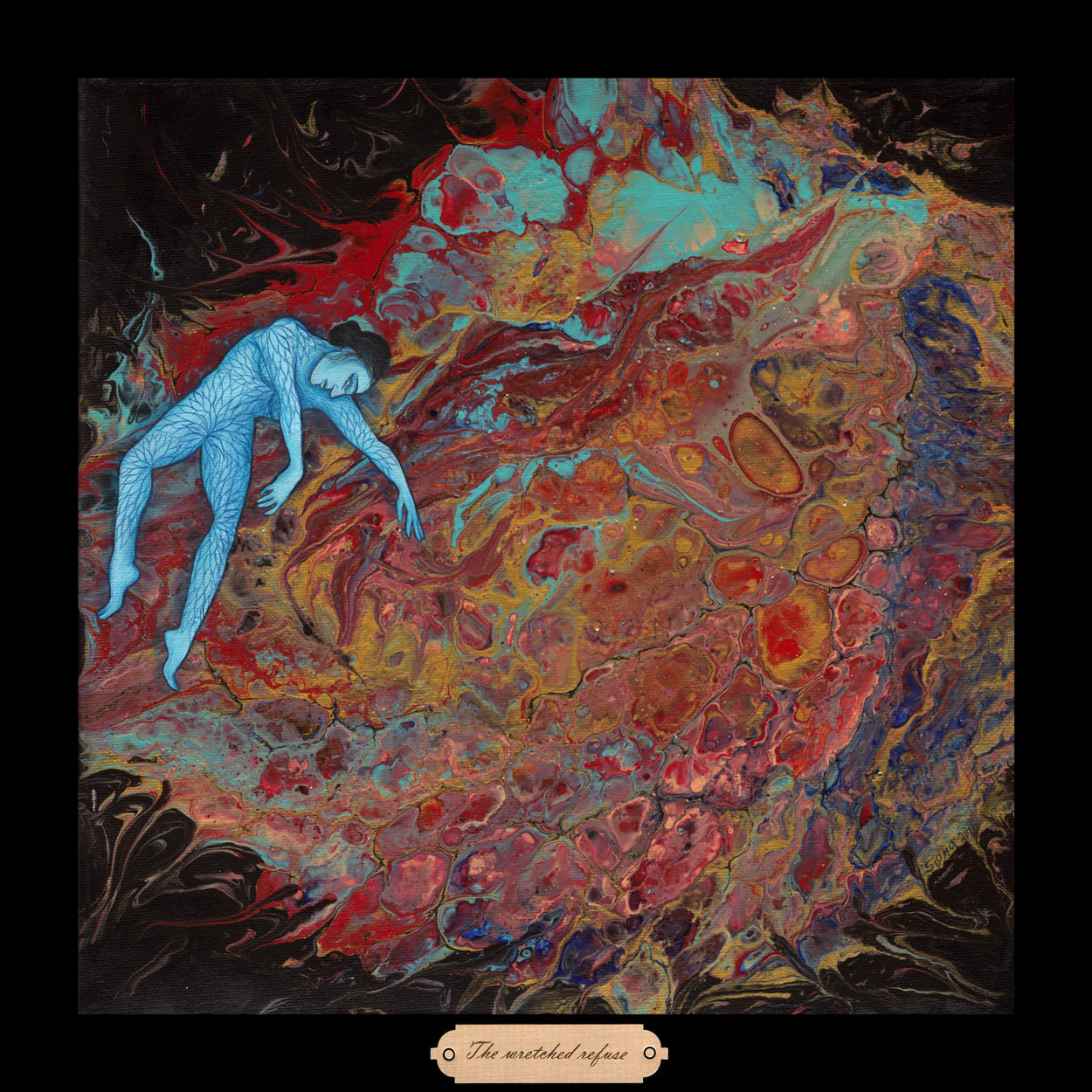

As America celebrates its independence on July 4, we commemorate the national holiday with a work by Indian-American artist Siona Benjamin, originally from Mumbai, India and now residing in the New York area. Her exhibition, Beyond Borders: The Art of Siona Benjamin, is on view at the Skirball Museum through July 30. The artist’s personal and unique take on the concept of Liberty is both compelling and poignant.

Liberty series

The Wretched Refuse

Siona Benjamin

Acrylic on canvas, from an installation of 14 paintings

2018

In 1883, Jewish poet Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” to raise funds for the construction of a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Her welcoming poem, intertwined with the fear and excitement that comes with journeying to a new land, encapsulates the hope and opportunity promised to those seeking a life in the United States. Consequently, “The New Colossus” became synonymous with the statue and the American dream. Despite the promises made by Lazarus and Lady Liberty, the United States has always had a complicated relationship with immigration. Unfortunately, the issue of America and immigration has reached a breaking point yet again with the worldwide refugee crisis and resurgence of white nationalist politics.

Responding to the fraught discourse about immigration, Benjamin explores the opportunities, hypocrisies, and contradictions of the American dream in her Liberty series. Each piece, titled at the bottom of the frame with a fragment of Lazarus’ poem, illuminates a different aspect of the migratory experience through vivid colors, abstract textures, and expressive figures.

In Siona Benjamin’s own words:

“My figures traverse foreign landscapes in search of a place to breathe freely. In this Liberty series, my textures and colors contrast with falling, crouching, flying, sleeping, tired, tempest tossed, homeless, and vulnerable bodies. Washed ashore or cast into the ocean, huddled or yearning to breathe free… again, or for the first time. These blue foreign bodies yearn to lift their lamps beside their own golden thresholds.”

Liberty series

The Wretched Refuse

Siona Benjamin

Acrylic on canvas, from an installation of 14 paintings

2018

June 2023

June 2023

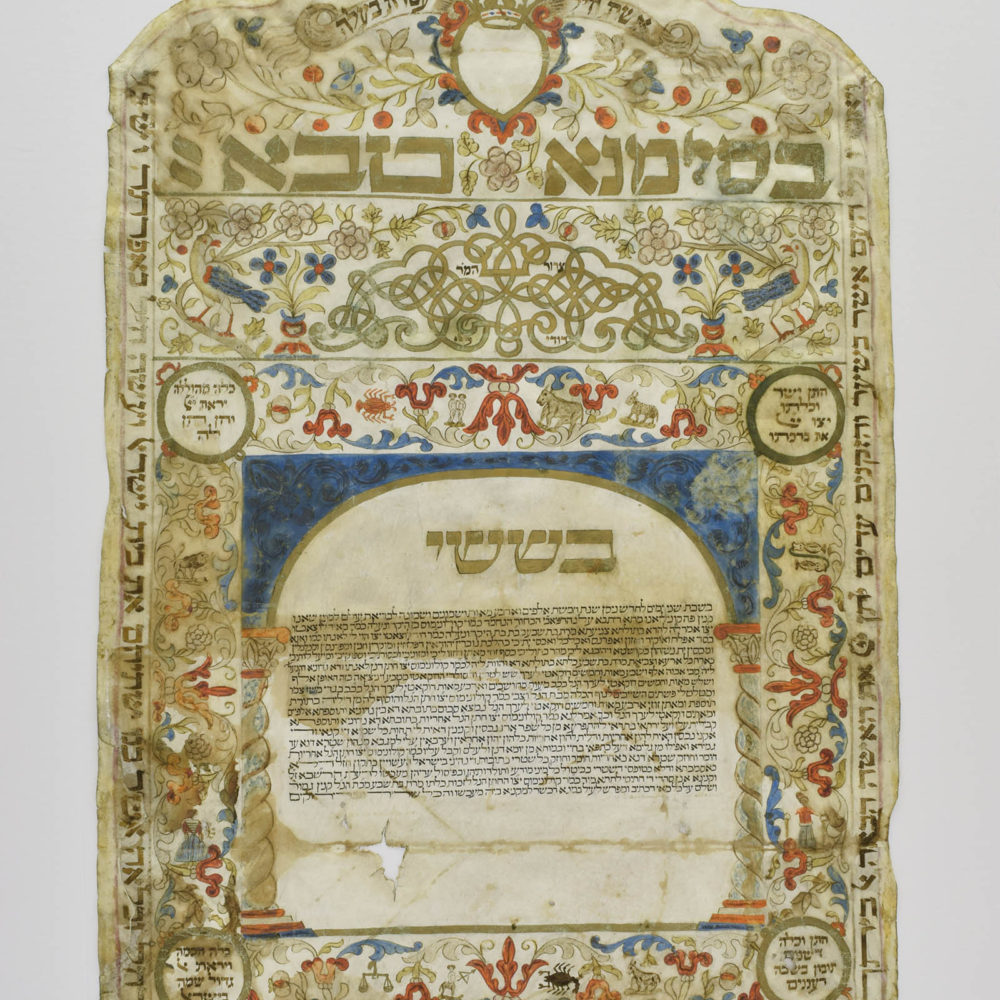

Ketubah (Marriage Contract)

Conegliano, Italy, 1728

Watercolor and ink on parchment, h. 29 x w. 21 ¼ in.

Cincinnati Skirball Museum, formerly S. Kirschstein collection, 34.45

The month of June is a popular time for weddings. In honor of that fact, this month’s object is a ketubah, or marriage contract. The ketubah is traditionally written in Aramaic, an ancient Semitic language related to Hebrew, Syriac, and Phoenician. The document stipulates the mutual marital pledges of husband and wife. Marriage is a sacred act in Jewish life. Since the first century B.C.E., writing an illuminated contract has been a significant custom, and its decoration has developed over the centuries into a fine art. A wide variety of themes, from family names and histories to stories of creation and floral designs, are found in these richly illuminated manuscripts. Central to the marriage ceremony is the reading aloud of the ketubah as prescribed in the book of Jeremiah: “The voice of joy and the voice of gladness, the voice of the bridegroom and the voice of the bride” (33:11).

The parchment of this ketubah is shaped along the upper border. The text in the lower section is framed by an arch supported by a pair of twisted columns reminiscent of the columns of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. Centered above the text, in monumental square characters heavily painted in gold, is the initial word “on Friday.” Around the border colorful tendrils are entwined with the signs of the zodiac, beginning with Aries, the sign of the first Hebrew month. In the four corners are gold roundels inscribed with a popular poem beginning with the words “the virtuous groom and his bride.” The initial Hebrew words in the upper segment are be-simana tova, meaning “with a good sign.” At the top, an empty crowned shield (apparently for the family’s coat of arms) is the centerpiece for an inscribed ribbon that bears the words from Proverbs: “a capable wife is a crown for her husband” (12:4). In the horizontal band below are birds, flowers, vases, and a knotted ribbon of myrrh, a reference to the Song and Solomon: “My beloved to me is a bundle of myrrh” (1:13). The popular text of Ruth 4:11 appears along the outermost edge: “Then the elders and all the people at the gate said, “We are witnesses. May the LORD make the woman who is coming into your home like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the family of Israel. May you have standing in Ephrathah and be famous in Bethlehem.”

The custom of making a ketubah continues to this day, with the couple to be married choosing decoration and imagery that is meaningful for their marriage. The ketubah is often hung prominently in the home as a daily reminder of the couple’s vows and responsibilities to each other.

Ketubah (Marriage Contract)

Conegliano, Italy, 1728

Watercolor and ink on parchment, h. 29 x w. 21 ¼ in.

Cincinnati Skirball Museum, formerly S. Kirschstein collection, 34.45

May 2023

May 2023

Every May, hundreds of organizations around the United States join together to help Americans of all backgrounds discover, explore, and celebrate the vibrant and varied American Jewish experience from the dawn of our nation to the present day. In celebration of Jewish American Heritage Month 2023, the Cincinnati Skirball Museum is pleased to highlight the work of Siona Benjamin, who has been making intricately detailed, transnational art with a feminist, Jewish, and political bent for almost two decades. Her distinct and unusual heritage as a descendant of the Bene Israel Jewish community of India informs her artistic perspective. Immigration, gender, the concept of “home”, and the role of art in social change are explored through vibrantly hued paintings. Her life and work tell a quintessentially Jewish American story. Beyond Borders: The Art of Siona Benjamin is on view at the Cincinnati Skirball Museum through July 30, 2023.

My America (2 pieces)

Siona Benjamin (b. 1960, Mumbai India), USA

Gouache and acrylic on paper and mixed media

2000-2001

This two-part installation is about looking inward and outward. Benjamin had recently received her American citizenship, which compelled her to make an American flag. She was also inspired by Jasper Johns’ celebrated American flag painting (1954-55). Her American flag, across the gallery wall, tells the story of immigration. Inside the red and white stripes of the flag, Benjamin includes many sacred cultural and religious icons such as handguns, World War II era American propaganda images of Bugs Bunny holding a warhead, the Statue of Liberty, and her resident alien card, which she had just relinquished to obtain her US citizenship.

A cast of Benjamin’s face, painted blue, looks at this American flag. She wears sunglasses, and a protective tallit surrounds her. Benjamin says: “Both helped me cope. The new immigrant accepts the reflection of all that is American in my oh-so-cool new American shades.”

April 2023

April 2023

Improvisation #25

Siona Benjamin (b. 1960)

Mixed media on museum board

2017

Siona Benjamin is an Indian American Jewish artist. Her art showcases her history, integrating Indian, Jewish, and American themes and imagery. One installation from her exhibition, Beyond Borders: The Art of Siona Benjamin, on view at the Skirball Museum April 20—July 30, 2023, features Lilith, a Jewish folk figure, dressed in Indian apparel, against a background reminiscent of American pop art and comic book illustration. Lilith is a prominent figure in her work, but she also integrates Indian goddesses. This weaving of narratives and aesthetics gives the artist’s work a unique and recognizable flair. These aspects of identity and history combine to form something new and beautiful.

Much of her work reflects her experience as a Jewish woman of color. She was raised Jewish in a mostly Hindu and Muslim part of India. She uses blue skin in much of her art both as an allusion to the Hindu goddess Krishna, and to represent her own experience of marginalization on the basis of race, religion, and gender.

In her Improvisation series, Siona creates art in a way “akin to musical improvisation.” This results in dynamic, provocative works which showcase the artist’s brilliance and mastery of media. In Improvisation #25, shown here, Siona plays on the character of Esther from the Hebrew Bible. The women depicted in the lower portion of the image represent Esther, with Siona Benjamin’s signature blue skin.

This Esther stands blindfolded beneath billowing clouds. Her name is written three times upside down in the upper right. As we look back at Purim and the story of Esther, we know that Esther becomes a hero when she refuses to hide. When her husband, the king of Persia, is convinced to issue an edict calling for the genocide of the Jewish people throughout his empire, Esther reveals herself as Jewish and advocates for her people. The revelation of her identity saves the entire Jewish people and secures Esther as a Jewish hero.

In this work, however, we see Esther as she is presented before that grand throne room scene. We see girls who have lost their vision, who remain hidden and generic. Esther was a displaced person who was trafficked into the king’s panoply of wives. Her blindfolded state reflects her lack of agency in that context. This work reminds the viewer that the great Queen Esther of

Chapter 8 of the Book of Esther is the same person as the powerless migrant girl of Chapter 2.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Thomas Carroll. He is a first-year student in Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Master of Arts in Jewish Studies in Cincinnati. He is excited to engage with the Skirball Museum for the 2022-2023 academic year.

Siona Benjamin (b. 1960)

Mixed media on museum board

2017

March 2023

March 2023

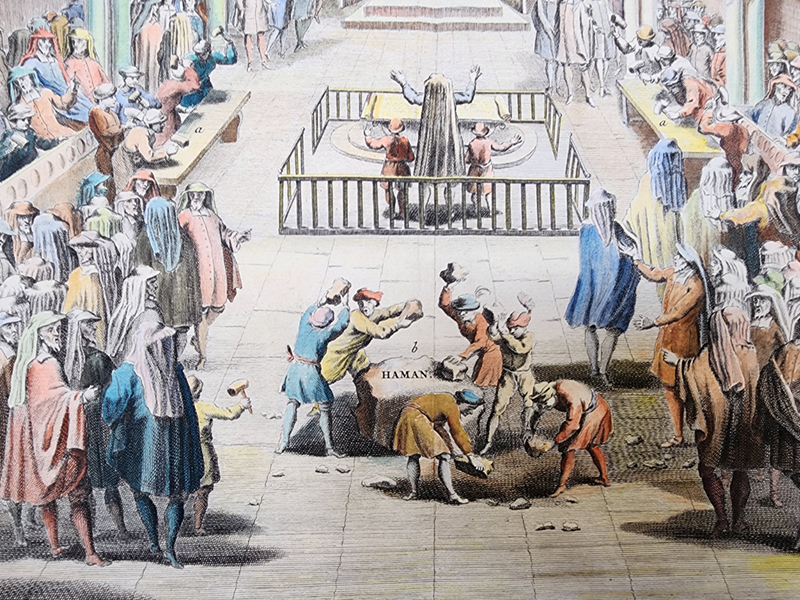

Purim Ceremonies in the Portuguese Synagogue, Amsterdam

Color engraving

Amsterdam, ca. 19th century

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection, Gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horowitz

This vibrantly colored engraving depicts the gathering of Portuguese Jews to hear the reading of the book of Esther on Purim. In the center, the reader passionately reads the Megillah. Below the reader, we see boys striking rocks on the stone labeled Haman as well as on the floor nearby. To the right, a lone hammerer also contributes to the noise. Throughout those gathered, various items are also used to make noise.

This dynamic energy recalls the carnival nature of Purim and of the book of Esther. The vibrant clothing and decadent building are reminiscent of the opulent Persian court of the book. The drama of the reader’s raised arms and the violence of the noisemaking echo the high stakes and drama of the book of Esther. This drama also reflects the modern understanding of Purim as one of the more ‘festive’ of the Jewish festivals.

Object ID: TCW 0028

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Thomas Carroll. He is a first-year student in Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Master of Arts in Jewish Studies in Cincinnati. He is excited to engage with the Skirball Museum for the 2022-2023 academic year.

Color engraving

Amsterdam, ca. 19th century

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection, Gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horowitz

February 2023

February 2023

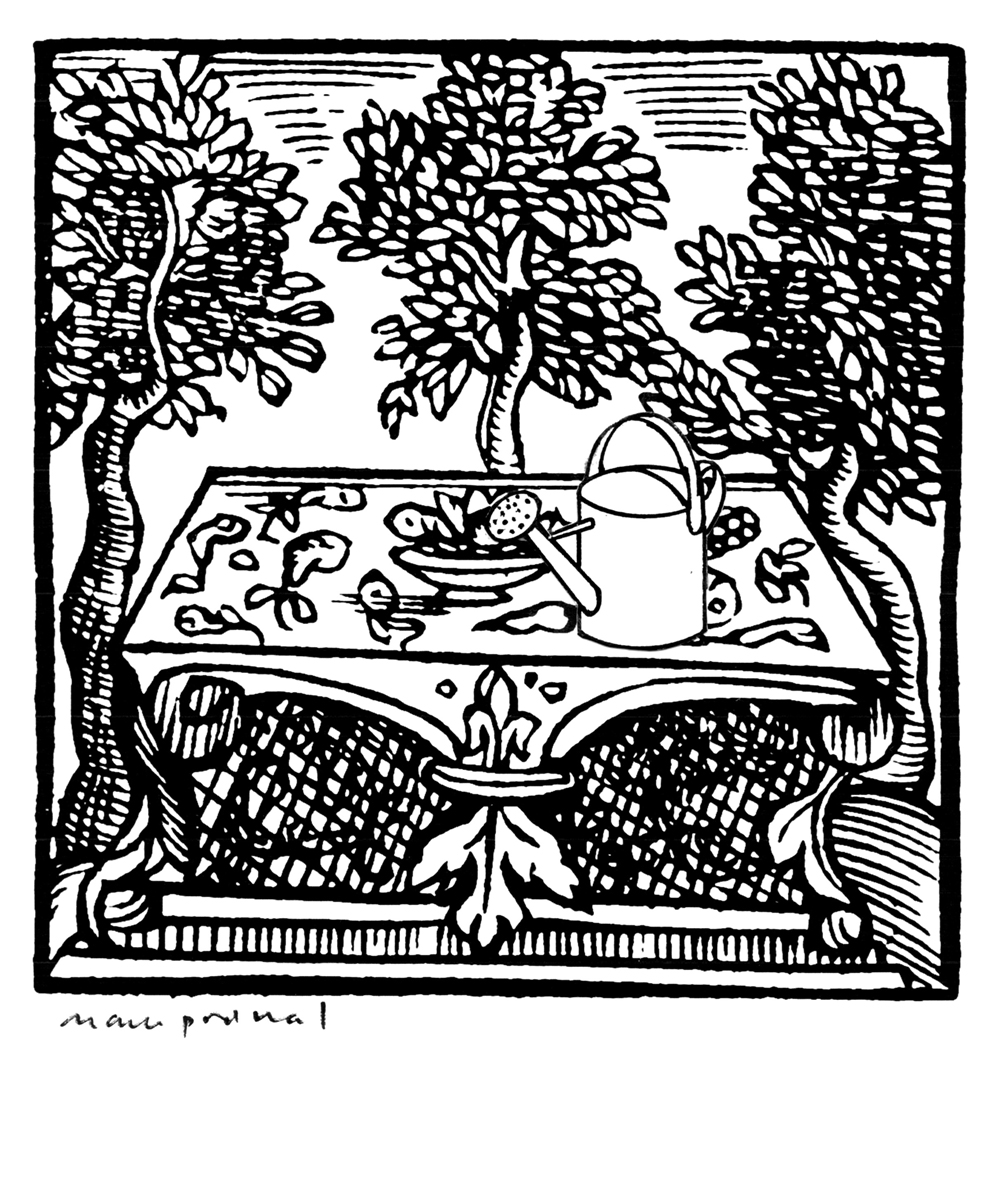

Tu B’Shevat, Mark Podwal (b. 1945), digital archival pigment print on paper 7 7/16 x 7 9/16″ USA, 2020

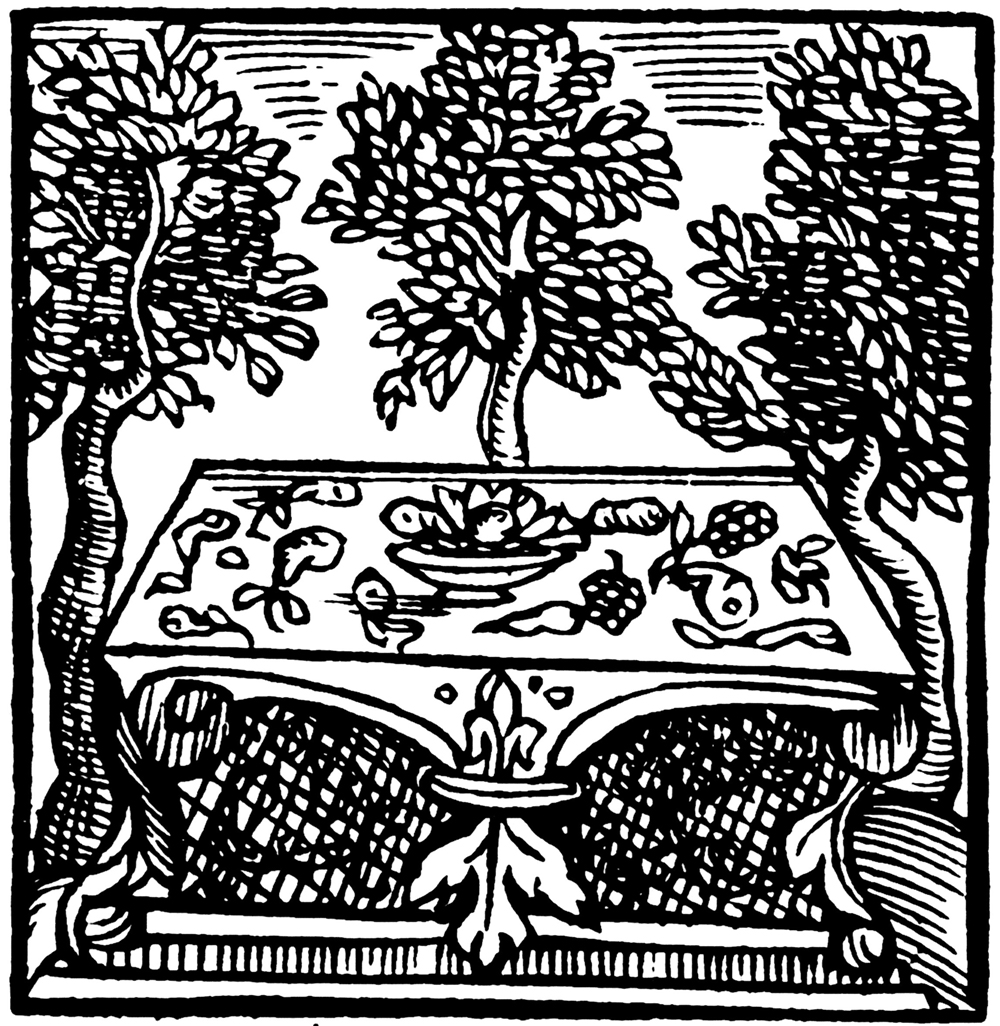

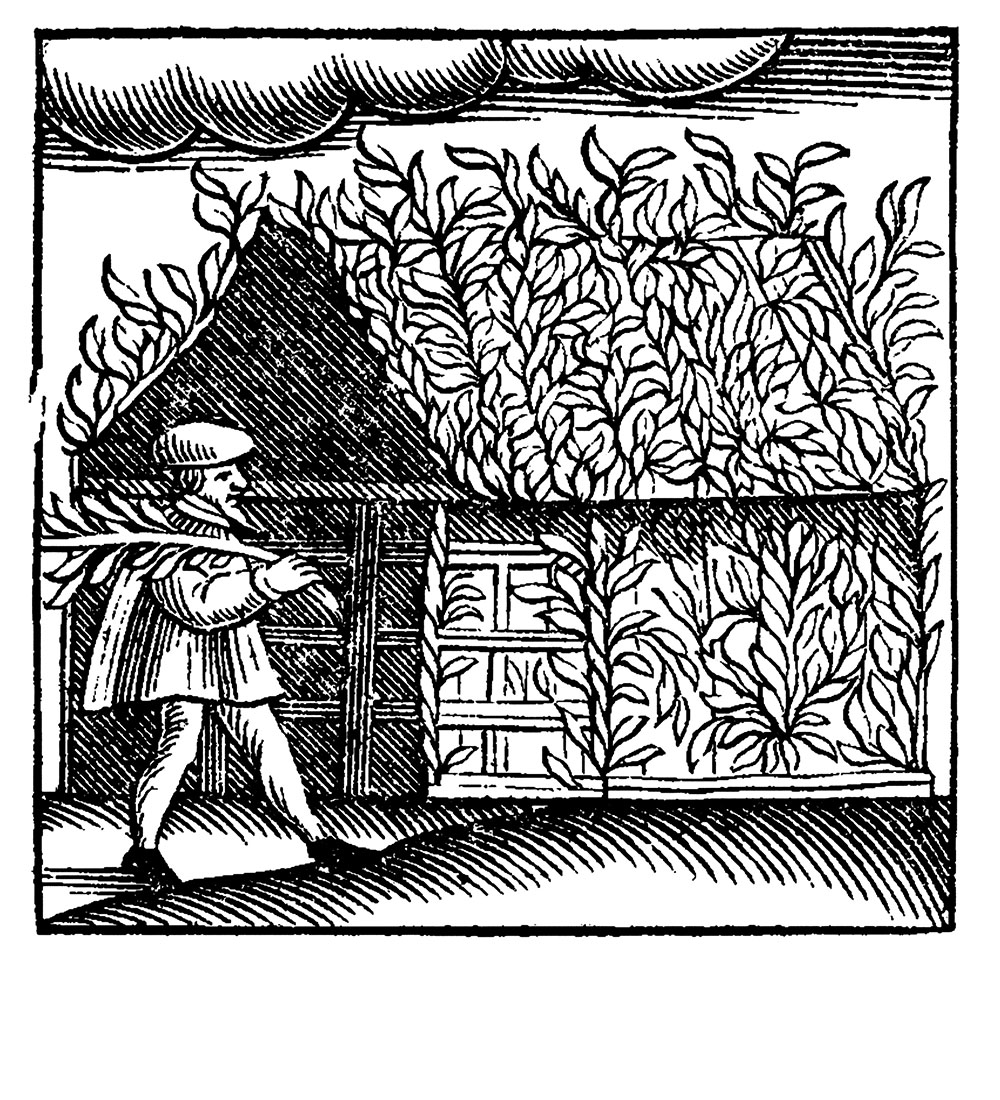

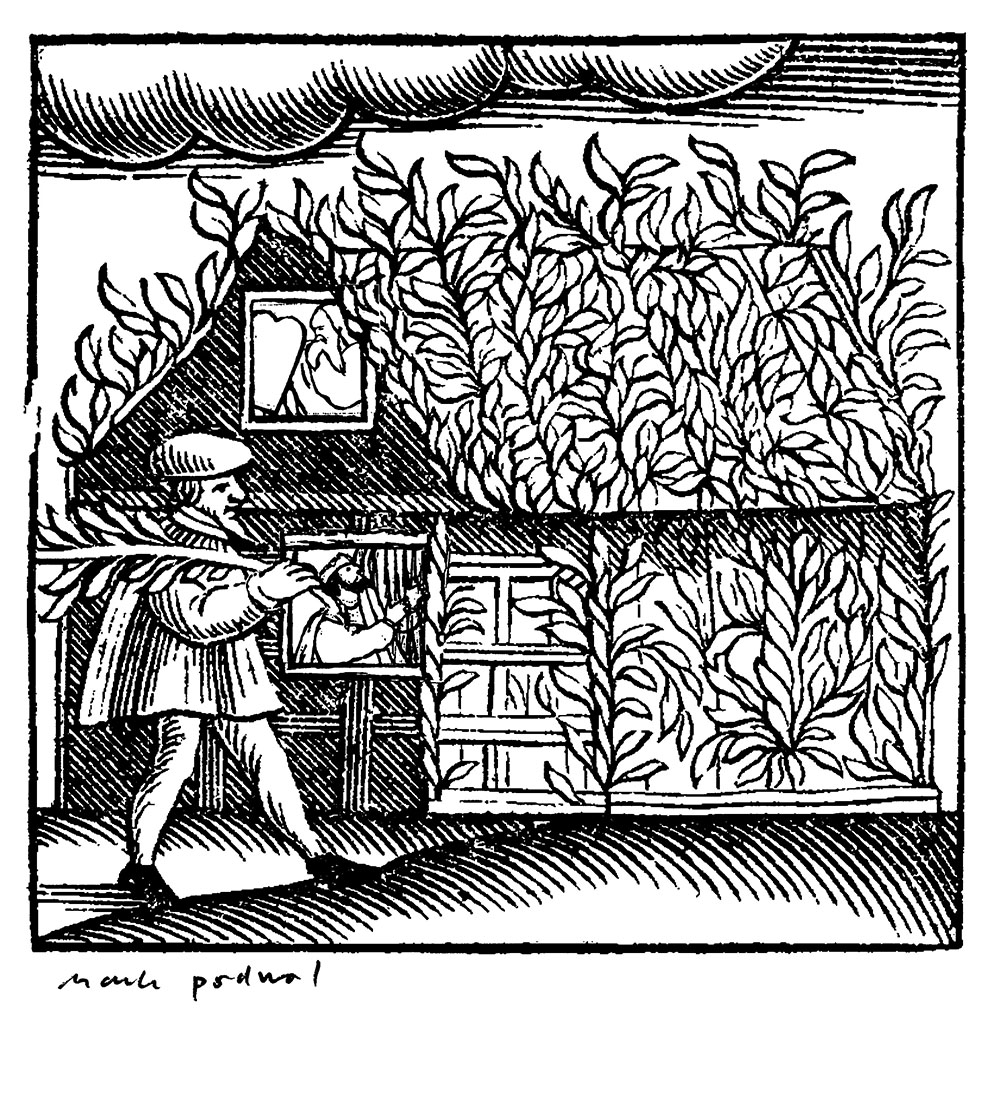

Tu B’Shevat, Sefer Minhagim, Venice, Italy, 1593

Tu B’shevat is a minor holiday celebrated on the fifteenth day of the month of Shevat. This year, it falls on February 5-6. It is the New Year of the Trees, one of four new years’ days given in the Mishnah, in the first passage of tractate Rosh Hashanah. The Mishnah is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions and the first major work of rabbinic literature. The new year for the trees was used to determine which tree-grown produce was eligible for which year’s tithe, and it also brings to mind the cycles of nature and the effects of time on the natural world. In his print series, A Collage of Customs, artist Mark Podwal (b. 1945) integrates modern elements into woodcuts from a Sefer Minhagim, or Book of Custom, published in Venice, Italy in 1593. In his adaptation of the woodcut for Tu B’shevat, Podwal has integrated a watering can into the image, which originally featured only a table with fruit shaded by trees.

Perhaps this indicates the role of humankind in maintaining the earth. It could also indicate the importance of water to ecology, reflecting on the need to preserve water as one of our most precious resources.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Thomas Carroll. He is a first-year student in Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Master of Arts in Jewish Studies in Cincinnati. He is excited to engage with the Skirball Museum for the 2022-2023 academic year.

Tu B’Shevat, Mark Podwal (b. 1945), digital archival pigment print on paper 7 7/16 x 7 9/16″ USA, 2020

Tu B’Shevat, Sefer Minhagim, Venice, Italy, 1593

January 2023

January 2023

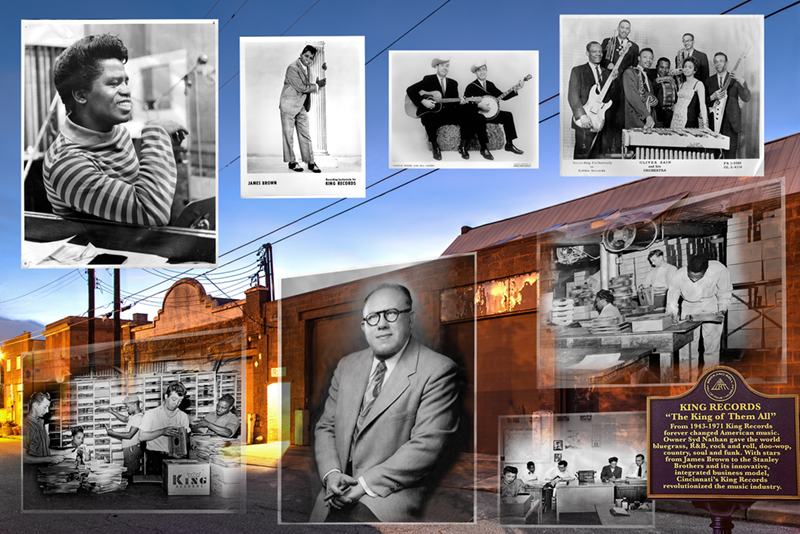

Syd Nathan and King Records, Cincinnati, 1943-1968

Digital chromogenic print, J. Miles Wolf © 2022.

In this last month of the Skirball’s special exhibition, “Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record by J. Miles Wolf, we feature a collage that tells the story of Syd Nathan and King Records. Photographer J. Miles Wolf blended the actual location of King Records in Evanston with photographs from the collections of Steve Halper and King Studios. The exhibition closes January 29.

King Records was founded by Syd Nathan in 1943. King Records did all of their work out of their Evanston location where they recorded musical acts, mastered the sound, pressed the records, and distributed them around the country. They were involved in many kinds of music from country, R&B, jazz, blues and funk. One of King Records’ most notable artists was James Brown who recorded the song “Please, Please, Please” with the label in 1956. It would go on to sell over three million copies, and kick start the funk legend’s career. The record label is responsible for other musical artists such as Hank Ballard, Otis Williams, The Dominos, Little Willie John and many more. Local music legends Bootsy Collins and Phillip Paul also recorded there.

Syd Nathan was born in Cincinnati to Jewish parents, Frieda and Nathaniel Nathan on April 27, 1903. As Syd Nathan grew, his vision regressed each year. It became so bad that he dropped out of school in the ninth grade. His impairment became his motivation to realize his ambitions, leading him to be quite the entrepreneur. He started King Records on a few borrowed dollars and grew it into a multi-million-dollar business.

King Records became the sixth largest record company in the United States, capable of pressing one million records per month. King records was the first racially integrated workplace in the city of Cincinnati, where twenty percent of its staff was African American. After passing in 1968, Syd Nathan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997. The studio building has just been added to the National Registry of Historic Places and is located in the Evanston neighborhood of Cincinnati. There are plans to transform the building into a community cultural space.

Syd Nathan and King Records, Cincinnati, 1943-1968

Digital chromogenic print, J. Miles Wolf © 2022.

December 2022

December 2022

Ruth Gruber

Eugene Daub (b. 1942)

Bronze

United States, 2022

Jewish American Hall of Fame Collection of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

Gift of Mel and Esther Wacks, Debra Wacks, and Shari Wacks

Ruth Gruber was born in 1911 to Russian immigrants living in Brooklyn, New York. After completing an undergraduate degree at New York University and a master’s at University of Wisconsin-Madison, she received a fellowship to study modern literature and art history in Cologne, Germany. There, she was awarded her Ph.D. in German literature at the age of 20, making her the youngest doctoral recipient in the world, according to The New York Times.

While studying in Germany, she attended Nazi rallies and wrote about her experiences as a Jewish American at anti-American, antisemitic demonstrations. After returning to the United States, she wrote for the New York Herald Tribune before being made a field representative of the Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes.

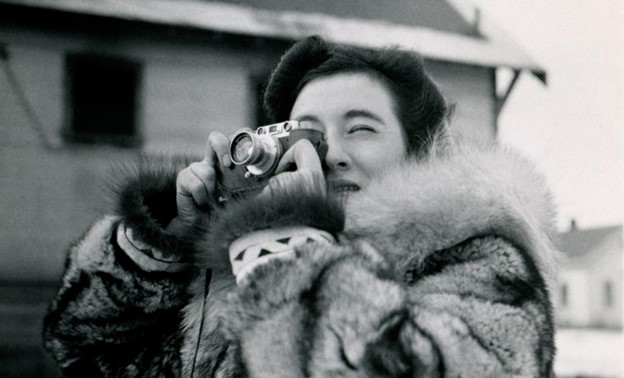

This photo of Ruth Gruber was taken by an unidentified photographer in Alaska (c. 1942). As field representative for Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Gruber undertook a social and economic study of Alaska, then a United States territory, before it was opened for homesteaders and veterans after World War II.

In 1944, Ickes selected Gruber for a mission to bring 1,000 World War II refugees from Naples, Italy to Fort Ontario, New York. Gruber personally flew to Europe to escort the refugees. After they had arrived in the United States, she used her influence as a journalist and government agent to lobby against the refugees’ deportation. Eventually, the refugees were allowed to apply for American residency. This was the only attempt by the United States to shelter Jewish refugees during World War II.

In 1946, Gruber left governmental work to pursue journalism again, reporting for the New York Post on conditions in British Palestine during the establishment of the state of Israel. After visiting displaced person camps in Germany, she went to Palestine, where she was introduced to the founders of Israel. Her work was crucial in bringing leaders such as David Ben-Gurion to the attention of American-Jewish readers as they worked toward a modern Jewish state.

In 1947, she began acting as a foreign correspondent for New York Herald Tribune. She traveled with the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine throughout Europe and the Middle East. While in Jerusalem, she learned of the Exodus 1947, a ship carrying about 4,500 survivors of the Holocaust as a part of the post-war Jewish immigration to Palestine. The ship was intercepted by the British navy, and the immigrants were forced to return to Germany. Gruber covered the story for the Herald, and her photos of the prisoners aboard deportation ship Runnymede Park were published by the Herald, bringing global attention to the story.

Ruth Gruber is the 2022 Jewish-American Hall of Fame honoree. Her medal joins the collection recently gifted to the Skirball Museum. An installation honoring Ruth Gruber is currently on view in the lobby of Mayerson Hall, the building that houses the Skirball Museum.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Thomas Carroll. He is a first-year student in Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Master of Arts in Jewish Studies in Cincinnati. He is excited to engage with the Skirball Museum for the 2022-2023 academic year.

Ruth Gruber

Eugene Daub (b. 1942)

Bronze

United States, 2022

Jewish American Hall of Fame Collection of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

Gift of Mel and Esther Wacks, Debra Wacks, and Shari Wacks

November 2022

November 2022

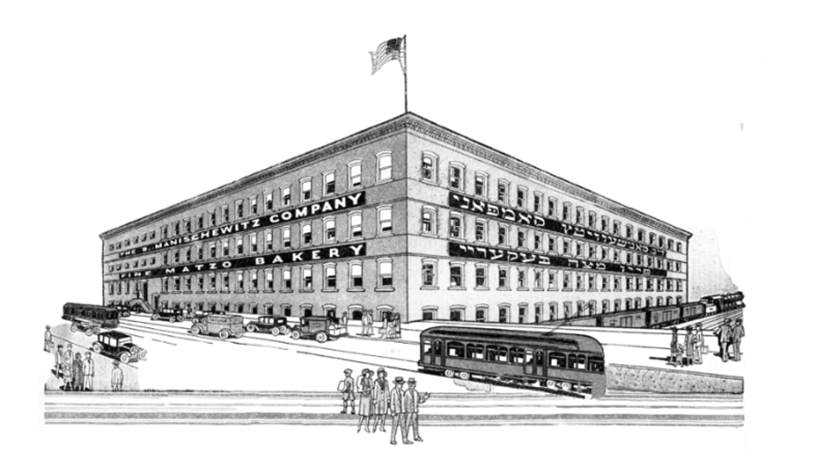

Manischewitz Factory Prayer Room Door

Wooden door with reverse glass painting

Cincinnati, ca. 1930

Gift of Kent Dobbins

The B. Manischewitz Company traces its beginnings to the spring of 1888, when Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz opened a small matzo bakery in Cincinnati, Ohio. The bakery was located on West Sixth Street. The main production plant was on West Eighth Street, east of Depot Street in the Price Hill neighborhood. At that time, railroad tracks ran to the east of the building. Part of the building still stands today.

In 2019, the Skirball was approached by a tenant in the building who had found a door with a glass insert that carried Hebrew writing and a logo with a Star of David surrounded by a pair of lions. The tenant knew that the building had once been the Manischewitz matzo factory. A visit to the site confirmed that the door was decorated with a version of the early company trademark. The banner above the Star of David reads “next year in Jerusalem” and the Hebrew inside the star reads “house of prayer”. Such a room for prayer would have been a necessity for an Orthodox establishment, as observant Jews pray three times a day. The reverse glass painting has been recently conserved by Fine Arts Conservation, Inc. and the door has been sanded and painted.

The Manischewitz Company, no longer family owned, is now headquartered in Newark, New Jersey. The Skirball Museum is proud to display this artifact of the company’s Cincinnati history. It was at the Price Hill factory that Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz automated the baking process and began packaging his matzos for shipment worldwide. A wooden box which can be seen in the museum’s collection held the early square-shaped matzo that revolutionized the industry.

The Manischewitz Door was recently added to the 3rd floor gallery of the Skirball Museum. The installation was timed to coincide with the Skirball’s current exhibition, “Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record by J. Miles Wolf,” which features a collage about the B. Manischewitz Company. The exhibition is on view through January 29, 2023.

Manischewitz Factory Prayer Room Door

Wooden door with reverse glass painting

Cincinnati, ca. 1930

Gift of Kent Dobbins

October 2022

October 2022

Ushpizin, Sefer Minhagim, woodcut, Venice, Italy, 1593

Ushpizin, Mark Podwal, archival print, New York, 2020

The High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, are followed a week later by a weeklong harvest festival, called Sukkot or “booths.” Sukkot not only reflects joy in the physical bounty of God’s creation, but also reminds Jews of the long period of ancestral wanderings in the wilderness between Egypt and the Promised Land – during which time the Israelites sojourned in temporary dwellings. Jews are commanded to build fragile structures (booths) and to eat and even sleep in them all week, in order to experience the past as if it were present. These booths are modeled after the huts of harvest workers and are roofed with branches cut from trees and vines. However, as artist Mark Powal reminds us, the customary interpretation of a sukkah is anachronistic, as tents would have been more likely than booths in the wilderness. Perhaps the Israelites initially cele- brated the festival in tents, which were later replaced by the sukkah. Or perhaps the Israelites assimilated a Canaanite custom of observing a seven-day festival by constructing booths, which in Canaanite practice served as pavilions erected for various deities. Whatever the origin, on entering the sukkah on Sukkot, rituals begin by inviting the ushpizin (Aramaic for “guests”)—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Aaron, and David. According to tradition, these seven guests will accompany the Messiah at the time of the final Redemption. A more recent custom also invites seven female ushpizot: Sarah, Rachel, Rebecca, Leah, Miriam, Abigail, and Esther.

The two images featured this month are a woodcut from a sixteenth-century Sefer Minhagim (Book of Customs) and an archival print by Mark Podwal in which the artist appropriates the original image and adapts it for the twenty-first century. Notice where he has added the likenesses of Moses with the Tablets of the Law, and David with his harp.

Ushpizin, Sefer Minhagim, woodcut, Venice, Italy, 1593

Ushpizin, Mark Podwal, archival print, New York, 2020

September 2022

September 2022

Rosh Hashanah

Chaim Gross (Austria 1904-1991 New York)

United States

Lithograph, 1967

Gift of Renee and Chaim Gross, 66.2738 a

Rosh Hashanah literally means head of the year and is the holiday that marks the beginning of a new year in the Jewish calendar. This year, Rosh Hashanah begins at sundown on September 25.

In honor of the Jewish New Year, our object of the month is a lithograph created by Chaim Gross. The artist was born in the Carpathian Mountain region of Austrian Galicia. He spent his first decade steeped in the traditions of Orthodox Jewish life. After his parents were violently attacked by Russian troops, he fled, and by 1921 was in New York. Once there, Gross studied at the Educational Alliance, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, and at the Art Students League. He was a prolific draftsman, painter, and printmaker, as well as a sculptor, and he was a beloved teacher as well.

This lithograph is part of a suite of ten original lithographs, plus a title page, depicting the Jewish Holidays. The artist’s Orthodox upbringing is reflected in the bearded faces of two men, heads covered with prayer shawls, blowing the shofar, or ram’s horn. The horn is blown to awaken the individual to personal responsibilities, both ethical and ritual. The commandment to sound the shofar is found in Leviticus: “In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts” (Lev. 23:24), and in Numbers: “You shall observe it as a day when the horn is sounded” (Num. 29:1). A swirl of imagery, some highly colored and some indicated only in pencil, includes additional faces, an upraised hand, the Hebrew letters spelling Rosh Hashanah, and a candelabrum.

Chaim Gross is best remembered as one of America’s foremost sculptors, known for his hardwood carvings, figurative sculptures, and graphic work. He is also considered one of the pioneers of the direct carving method.

Rosh Hashanah

Chaim Gross (Austria 1904-1991 New York)

United States

Lithograph, 1967

Gift of Renee and Chaim Gross, 66.2738 a

August 2022

August 2022

Judaean Coin

Judaea, 134-135 CE

Silver, 1-1/64”

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection; gift of Daniel Grossman, 1986.002

Tisha B’Av, (תשעה באב), the Ninth of Av, is a Jewish day of mourning that falls this year on August 6th and 7th. As referenced in July’s object of the month, the day is preceded by three weeks of mourning, beginning on the seventeenth of Tammuz. Like the Seventeenth of Tammuz, Tisha B’Av is a fasting day on which food and drinks are not consumed. Traditionally, bathing, washing, wearing leather shoes, and entertainment are prohibited as well on this day.

These observances are done to commemorate five tragedies that occurred on the ninth of Av throughout Jewish history. The biblical book of Numbers 13:1-33 recounts that on this day, spies dissuaded the Israelites from entering Canaan through their lack of faith. For their incredulity, the Israelites were sent to wander in the desert for forty years, never reaching the Promised Land. On the ninth of Av in 586 BCE, the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar, and his armies destroyed the first Holy Temple and expulsed the Kingdom of Judah–sending them into Babylonian exile. In 70 CE, the Romans destroyed the Second Temple, and–just as Nebuchadnezzar did more than six-hundred years earlier–exiled the Jewish people from the Holy Land and began the Jewish Diaspora.

The last two tragedies remembered on Tisha B’Av occurred on the same year, 135 CE. These two tragedies both relate to Bar Kochba’s revolt–an uprising led by Simon bar Kochba during the Roman Imperial rule of Judaea. During this time, tensions between Judaeans and Romans were escalating. The increase of Roman military presence in the area, as well as the dedication of a temple built on the Temple Mount to the Roman god Jupiter, and the development of a neighboring Roman colony (Aelia Capitolina) on the ruins of Jerusalem, were all driving forces behind the Judaean rebellion. Although the revolt lasted for four years, it was ultimately quashed by the Roman imperial military in 135 CE. The defeat was devasting to the Judaeans–hundreds of thousands were murdered and the fortified city of Beitar was destroyed. With the end of the revolt, the temple site in Jerusalem and its surroundings were plowed. These events are commemorated on Tisha B’Av, and annually mourned by Jews around the world.

August’s object of the month is a Judaean “sela” coin, which was overstruck on a Roman tetradrachm from the time of the Bar Kochba revolt. Tetradrachms are large, silver coins that were popular as currencies throughout Mediterranean society before the 4th century. The obverse of this Judaean coin is a contemporary depiction of the Jerusalem temple’s façade beneath a star (a reference to the meaning of Bar Kochba’s name, “Son of the Star”), the tablets of the Ark of the Covenant, a horizontal ladder indicating an ascension to the altar, and an ancient inscription of “Shimeon,”–Bar Kochba’s name. The coin’s reverse depicts a lulav and etrog surrounded by an inscription in ancient Hebrew reading “for the freedom of Jerusalem.” This coin was likely minted in the time after the Roman capture of the Judaean capital city—the imagery a bittersweet reminder of Jerusalem.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Natalie Taylor. She is currently a third-year undergraduate student at Sarah Lawrence College in New York and is passionate about Jewish art history. Natalie has been excited to engage with the museum for the summer of 2022

Judaean Coin

Judaea, 134-135 CE

Silver, 1 1/64”

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection; gift of Daniel Grossman, 1986.002

July 2022

July 2022

The Golden Calf

Mustafa Al-Khatib

Jerusalem, 2007-2010

Paint and pencil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 27 1/8”

A gift from the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities in Israel, 2016.15.129

July’s object of the month is a part of the Skirball’s collection, Children of Jerusalem: Painting Pain Dreaming Peace. This collection features works created by elementary school children residing in Jerusalem — Arabs and Jews, Palestinians and Israelis — throughout the course of a three-year curriculum led by the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities in Israel. Just as this program allowed a shared artistic experience for children of different religions, both the Quran and the Torah share in the story of the golden calf, which has here been depicted by Mustafa Al-Khatib, an artist who is not Jewish, for this July’s object of the month.

The Golden Calf illustrates a colorful landscape – a vibrant blue sky, rolling blue mountains, a horizon of warm green trees, and a deep green field outstretching to the canvas’ lower edges. Centered on this field, placed in the middle of a ring of orange and red flames, is a calf. Its gold surface and red eyes indicate the depicted calf not to be a living animal, but rather a crafted idol resembling a calf.

This subject matter, the idol of a golden calf, connects The Golden Calf to the thirty-second chapter of Exodus. This section of the Torah immediately follows the forty days and forty nights that Moses spent on Mount Sinai, receiving the tablets of testimony away from his followers, the Israelites. Uncertain of Moses’ condition on top of the mountain, his brother, Aaron led the Israelites in collecting their gold and melting it down into an idol (such as that in The Golden Calf). The next day, they worshipped the idol, offering sacrifices and dancing around the calf. Moses became alerted to the Israelites’ actions, and he descended Mount Sinai. When he saw the idolatry for himself, Moses became enraged and threw the tablets to the ground, shattering them.

This act, Moses’ breaking of the tablets, is commemorated every year with the observance of Shivah Asar B’Tammuz (שבעה עשר בתמוז), the seventeenth day of the Hebrew month Tammuz. This year, the observance is held on July 17th (in accordance with Shabbat on July 16th). The Seventeenth of Tammuz is a minor fasting holiday, where, traditionally, food and drinks are not consumed for the duration of the day. This day not only commemorates the destruction of the tablets, but also four other calamities that occurred on the seventeenth of Tammuz over the years: the burning of Torah scrolls by Roman military leader Apostomus, his placement of an idol in the Temple, the ceasing of burnt offerings, and the breaching of the walls of Jerusalem before the destruction of the Second Temple.

The Seventeenth of Tammuz also marks the beginning of the three-week mourning period preceding the Tisha B’Av (תשעה באב), the ninth day of the Hebrew month of Av. Tisha B’Av which commemorates five other calamities, including the destruction of the Second Temple soon after the breaching of Jerusalem’s walls on the seventeenth of Tammuz.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Natalie Taylor. She is currently a third-year undergraduate student at Sarah Lawrence College in New York and is passionate about Jewish art history. Natalie has been excited to engage with the museum for the summer of 2022.

The Golden Calf

Mustafa Al-Khatib

Jerusalem, 2007-2010

Paint and pencil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 27 1/8”

A gift from the Institute for the Study of Religions and Communities in Israel, 2016.15.129

June 2022

June 2022

Shira Hadasha

Laurie Gross, USA, 2021

Archival photo print, bronze, handwoven and dyed linen and gold hand embroidery, metallic fabric with machine embroidery, 30” x 24” x 1”

On loan from the artist to the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

Fifty years ago, on June 3, 1972, the first North American female rabbi, Sally Priesand, was ordained by Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, Ohio. In the decades since her ordination, many other women rabbis have followed the path that she pioneered, contributing their own diverse life stories to the rabbinate. Holy Sparks, the Cincinnati Skirball Museum’s latest exhibition, shines a light onto twenty-four trailblazing women rabbis whose experiences, challenges, and achievements serve as inspiration for Jewish women everywhere.

For the Holy Sparks exhibition, on view through September 4, 2022, twenty-four Jewish women artists have created works inspired by interviews produced by the Braid’s Story Archive of Women Rabbis and preserved by the Jewish Women’s Archive. This exhibition transforms the rabbis’ lived experiences, knowledge, and ambitions through the aesthetic visions and the creativity of contemporary artists.

Shira Hadasha by Laurie Gross was one of the works created for the Holy Sparks exhibition. Gross is a nationally recognized artist who creates profound Jewish artwork, often collaborating with her family. Her Judaica incorporates midrash (commentary) and scripture with Jewish tradition and culture. Shira Hadasha combines these elements through the inspiration of Rabbi Angela Warnick Buchdahl’s life story.

Shira Hadasha is centered around seven bronze representations of the Hebrew letter shin — a repetitive allusion to the meditative nature of Divine presence. Underneath these letters is a bursting, dynamic blue and white background, which itself is a piece of the Torah Ark tapestry from Central Synagogue in New York City, where Rabbi Buchdahl serves as Senior Rabbi. Surrounding this piece of tapestry is a linen border, embroidered with handwoven text. Across the top, in Hebrew, is Gross’s artistic interpretation of Psalm 96, “We are compelled to sing a new song, one that speaks to us and renews us,” (“שירו ליי שיר חדש”). Below this, across the bottom, is the phrase “חזק חזק ונתחזק” (be strong, be strong and let us be strengthened) which is bordered by the Korean words “산, 물, 노래” (“mountain, water, song”). These ideas of religious strength and song are evocative of Rabbi Buchdahl herself.

Shira Hadasha weaves together Rabbi Buchdahl’s Jewish and Korean identity through powerful text and meaningful symbols – expressing her life story through art. With her role as Senior Cantor for Central Synagogue, Rabbi Buchdahl became the first Asian American to be ordained as a cantor in North America and, she now serves as her congregation’s first female rabbi in their one-hundred-eighty-year history. Through her work, Central Synagogue has become a prominent force in interfaith movements for racial equity and criminal justice reform. Gross’s piece expresses Rabbi Buchdahl’s initiative and the strength that she demonstrates as a rabbi.

This Object of the Month entry was written by Cincinnati Skirball Museum intern Natalie Taylor. She is currently a third-year undergraduate student at Sarah Lawrence College in New York and is passionate about Jewish art history. Natalie has been excited to engage with the museum for the summer of 2022.

Shira Hadasha

Laurie Gross, USA, 2021

Archival photo print, bronze, handwoven and dyed linen and gold hand embroidery, metallic fabric with machine embroidery, 30” x 24” x 1”

On loan from the artist to the Cincinnati Skirball Museum

May 2022

May 2022

May is Jewish American Heritage Month, when we celebrate the vibrancy and diversity of American Jewish life and the inextricable link between Jewish Americans and broader American history and culture. At the same time, we continue to celebrate the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial. This month’s entry is a medal that depicts a Cincinnati-born woman who became an important figure in public nursing and health care for immigrants at the end of the 19th century and in the early decades of the 20th century in America.

Learn more about the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial at https://www.jewishcincy200.org and Jewish American Heritage month at #OurShared Heritage and #JewishAmericanHeritageMonth!

Lillian Wald (1867-1940)

Virginia Janssen (b. Wisconsin, 1962)

USA, 2007

Bronze

Cincinnati Skirball Museum, Jewish-American Hall of Fame Collection, gift of Mel and Esther Wacks, Debra Wacks, and Sheri Wacks

After growing up in Cincinnati and New York, Lillian Wald enrolled at New York Hospital’s School of Nursing in 1889. She graduated from nursing school in 1891 and took courses at the Women’s Medical College, but by 1893 left school to help poor immigrant families in New York’s Lower East Side as a visiting nurse. Along with another nurse, Mary Brewster,

she created the Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service, which became the major model for visiting nursing in the United States and later the Henry Street Settlement. Around that time Wald coined the term “public health nurse” to describe nurses whose work is integrated into the public community. Her ideas led the New York Board of Health to organize the first public nursing system in the world. She was the first president of the National Organization for Public Health Nursing, established a nursing insurance partnership with Metropolitan Life Insurance

Company that became a model for many other corporate projects, and suggested a national health insurance plan. Wald helped to found the Columbia University School of Nursing and persuaded the New York City Board of Education to put nurses into public schools. The Henry Street Settlement still stands and now serves the neighborhood’s Asian, African-American, and Latino population. Today, the Visiting Nurse Service of New York is the largest not-for-profit home health care agency in the nation. In a speech to Vassar students in 1915, Wald encouraged the young women to serve the public. She quoted from Proverbs 31:20, “She reacheth forth her hands to the needy.” These words are inscribed on the medal issued when Lillian Wald was inducted into the Jewish-American Hall of Fame.

The Lillian Wald medal is currently on view in the lobby of Mayerson Hall, along with additional medals honoring Jewish American Hall of Famers with Cincinnati connections.

Lillian Wald (1867-1940)

Virginia Janssen (b. Wisconsin, 1962)

USA, 2007

Bronze

Cincinnati Skirball Museum, Jewish-American Hall of Fame Collection, gift of Mel and Esther Wacks, Debra Wacks, and Sheri Wacks

April 2022

April 2022

Charoset container

Silver

Germany, 19th century

Gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection

In my opinion, the tastiest part of Passover is not matzah (unleavened bread), maror (bitter herbs), or zeroa (lamb shank bone). Instead, it is the chunky, fruity, nutty stuff called charoset. Charoset is one of the foods that is placed on a special plate during the Passover seder (ritual service and ceremonial dinner) that symbolizes the brick and mortar the Jewish people used during their enslavement in Egypt thousands of years ago. This yummy dish reminds us of our hard work and redemption from the land of Egypt by the hand of God.

This month’s object is a miniature (1”x1.8”x4.75”) Passover condiment container that was used to hold the charoset during the Passover seder. It is in the shape of a tiny wheelbarrow, and it was a part of an entire silver set. The wheelbarrow reminds the Jewish people of the labors of their ancestors hauling bricks and mortar under Egyptian slavery.

One of the memories I have of my grandmother is her charoset recipe. As a little girl, I would stand next to her as she would cut up red apples into small chunks, add walnuts, cinnamon, and grape juice to a bowl. After it sat for a little bit, we would eat her charoset together by the spoonful. This simple, sweet treat made me love the holiday of Passover, and gain a precious memory of my grandmother before she passed away. Little did I know, this specific charoset recipe was not unique to my grandmother. The Ashkenazi (eastern European) custom of making this dish is almost the same as my grandmother’s recipe. This makes me wonder: what are the different charoset recipes used around the world by all the different types of Jews?

Iraqi charoset is known for its use of dates, since they are the native fruit of the region. Simply, the recipe calls for walnuts and a date-honey spread. After it is processed together, the charoset turns into a thick-honey spread that can be used with matzah and vegetables. Indian-style charoset has its own unique twist on the dish. Indian culture has turned this dish into a chutney that blends sweet and sour tastes. Mangos, raisins, dates, almonds, sugar, salt and red wine vinegar are processed together to make a delicious charoset the Indian Jewish community has come to love.

The variety of charoset recipes exemplifies the diversity of Jewish communities around the world. As it changes and adapts to different cultures and climates, it reminds everyone who eats it of their own history of redemption from Egyptian bondage and the freedoms they enjoy in their lives today. This Passover, we have the chance to discover our family’s charoset tradition or create our own. Whatever you decide, the outcome will be just as tasty as ever!

This entry was written by Ashley Englander, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR. She studied Religious Studies at the University of South Florida. She is currently the Student Intern for the Cincinnati Skirball Museum. Ashley has a passion for Jewish history, and she has been excited to engage with the exhibitions and programming at the museum for the 2021-2022 year.

Charoset container

Silver

Germany, 19th century

Gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection

March 2022

March 2022

Purim

Mark Podwal

Digital Archival Print 2021

The Talmud (Torah commentary and interpretation) shares the following story: Rabba (a 4th century scholar of Talmud) and Rabbi Zeira prepared a Purim feast with each other. On Purim, a person is obligated to drink wine during the holiday and become so intoxicated that he or she cannot distinguish between Haman and Mordechai. As it was commanded of them, both rabbis became very intoxicated. Rabba stood up and killed Rabbi Zeira. The next day, when he was sober and realized what he had done, Rabba asked God for mercy and to revive Rabbi Zeira. The next year, Rabba said to Rabbi Zeira, “Let God come and let us prepare the Purim feast with each other.” Rabbi Zeira responded, “Miracles do not happen each and every hour, and I do not want to undergo that experience again.” (BT.Megillah 7b)

Although our tradition commands us to drink and be merry during the holiday of Purim, it also teaches us to not celebrate in excess. Excess in any activity, although it might be fun in the moment, can be harmful to others or ourselves. On Purim, the Jewish people recall the fear of persecution from Haman (Boo!), who sought their destruction, and the miracle of salvation from God. After they were saved by Esther and Mordechai’s bravery, the Jewish people celebrated in the streets of Shushan. Although kids in religious school learn that the story of Purim ends there, it does not. King Ahasuerus decreed that the Jewish people could go out and slaughter anyone who went against them in the land. The Jewish people on the 13th of Adar killed 75,000 people in the land of Shushan. This topsy-turvy story appears silly and festive, but its dark ending challenges the Jewish people’s values. It might be seen as excessive for the Jewish people to have killed so many in their city. In our freedom and salvation, how shall we act towards those who wanted to harm us?

Mark Podwal’s reinterpretation of the woodcut found in Sifrei Minhagim (Books of Customs) for the festival of Purim is whimsical and inventive. The original woodcut portrays the men in costume carrying a paper sound maker in one hand and a wine jug in the other. Podwal’s collage adds a large wine bottle with a megillah (scroll of Esther) inside of it. This image emphasizes the silly and meaningful themes of Purim – drinking, dressing up in costumes, making noises, and reading from the megillah.

This Purim, just as Mark Podwal did with his collage, we can add elements into our Purim celebration that we may not have done in years past. For example, we can engage in matanot l’Evyonim – giving gifts/charity to the poor. Or, mishloach manot – exchanging gifts with friends. Let us add joy into our Purim festivities this year and remember to not be excessive in our actions. You don’t want to end up like Rabbi Zeira this year!

This entry was written by Ashley Englander, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR. She studied Religious Studies at the University of South Florida. She is currently the Student Intern for the Cincinnati Skirball Museum. Ashley has a passion for Jewish history, and she has been excited to engage with the exhibitions and programming at the museum for the 2021-2022 year.

Purim

Mark Podwal

Digital Archival Print 2021

February 2022

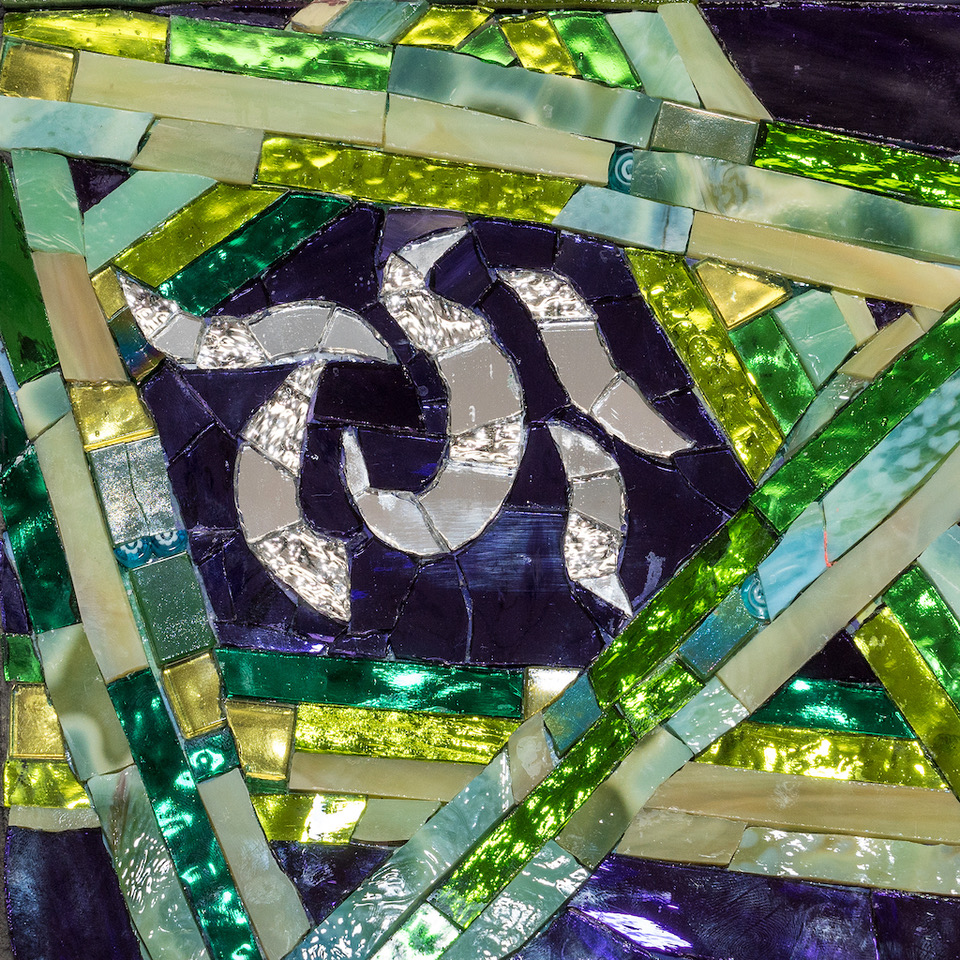

Remember

Carol Shelkin, Havertown, PA

Stained glass and mirrored glass, 2019

Between 1941 and 1945, the Holocaust took six million Jewish lives from our world. Today, we teach our children the horrors of the events and the antisemitism that existed before, during and after that time. As a Jewish people, we promise to ‘Never Forget’ what happened to us. Similarly, the Torah reminds us to never forget how we were once slaves in Egypt, thus we should welcome the stranger into our community. Our people understand what it means to be oppressed, so we strive to fight bigotry and hatred that sometimes rattles our communities.

In October of 2018, the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh, PA experienced one of the most devastating horrors of antisemitism in 21st century America. During Shabbat morning services, an anti-Semite entered the building and killed eleven people and injured six. Some of the victims were Holocaust survivors. A Jewish community was attacked and traumatized. Their pain and suffering were felt by Jews throughout the entire world. Our people experienced another deadly attack, and the words ‘Never Forget’ echoed in our ears. We remembered the agony of our ancestors from biblical times, the Middle Ages, the Holocaust, to now –in a country where we believe freedom of religion is an unalienable right.

Carol Shelkin of Havertown, PA designed a mosaic that was inspired by the Tree of Life Congregation attack of 2018. In the center of the tile is the Hebrew word Zachor, which means remember. ‘Remember’ is written to remind its audience that the lives lost on that day were not in vain. She approaches the question of ‘How can we make this world better because of the lives lost?’ Her answer is, ‘Teach our children to see others as human beings and never allow this to happen again.’

Antisemitism rattled the Jewish people again with the hostage takeover at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville TX on January 15th of 2022. Fortunately, all the victims were physically unharmed. However, the words ‘Never Again’ echoed in the ears of the entire Jewish people. Antisemitism has been on the rise in America and throughout the world for decades. We ask ourselves, ‘how can we battle the hatred that is visited upon our people and communities?’ While we are challenged with this question, we remember the lives taken by acts of antisemitism, hatred, and bigotry.

Let us remember those who are gone too soon from our lives, and may we continue to stand as one people united through courage, strength, and love.

Please visit the Skirball to see other beautiful mosaics in our exhibition, From Darkness to Light: Mosaics Inspired by Tragedy, on view February 24th through May 8th. The Tree of Life Synagogue Mosaic Project is the brainchild of Susan Ribnick, co-chair of the Austin Mosaic Guild in Texas. Just days after the horrific attack at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Ribnick was inspired to use her skills and passion as an artist to help her heal. She reached out to fellow mosaic artists and brought together 36 people from around the country and the world to create a collection of mosaics that react and respond to the Tree of Life massacre.

This entry was written by Ashley Englander, a fourth-year rabbinical student at HUC-JIR. She studied Religious Studies at the University of South Florida. She is currently the Student Intern for the Cincinnati Skirball Museum. Ashley has a passion for Jewish history, and she has been excited to engage with the exhibitions and programming at the museum for the 2021-2022 year.

.

Remember

Stained glass and mirrored glass, 2019

January 2022

January 2022

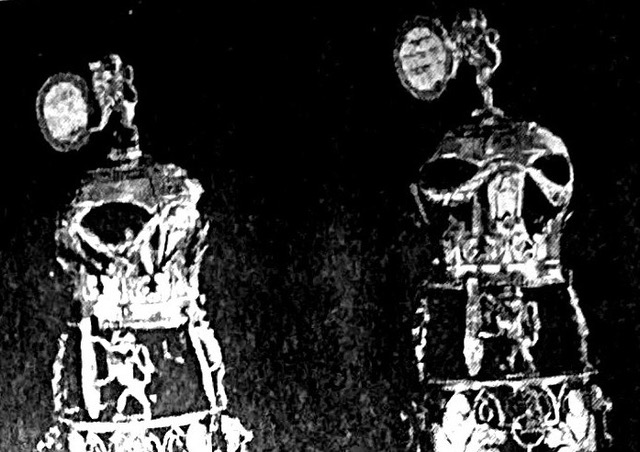

Torah Finials (Rimmonim)

Carl Bitzel (1749-1823)

Silver: repoussé, pierced, engraved, and cast; 18 1/16” inches/ 18 ¼” x diameter 4.92” inches

Augsburg (Germany) 1803

Hallmarks: City: Pine over “O” (=Augsburg 1803), Seling 287; Maker: “CB” in oval (=Carl Bitzel), Seling 2608

B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection of the Cincinnati Skirball Museum, gift of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz, 2015.17.430 a & b

During my fellowship stay at The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of Hebrew Union College-Institute of Religion, I was struck by these two rather large silver rimmonim (Torah finials), which have been part of the Skirball Museum´s collection since 2015. These extraordinary and impressive objects appealed to me not only because of their unusually beautiful artistic design and execution, but also because their provenance might be of interest for my own research on the post-WWII ‘afterlives’ of European Jewish ceremonial objects.

The material heritage of European Jewry was deeply affected by the mass looting and destruction before and during WWII. The “remnants” that survived the National Socialist regime’s war upon European Jewry had either been sent into “exile” for safekeeping before the war or ended up circulating in new settings after 1945 as a result of plunder, sale, or restitution. In order to clarify questions of origin and possible looting, recent provenance research has become an important sub-discipline of art history in its own right. Researching the provenance of an individual object means tracing its ownership history, which might also shed light more generally on its historical, social, and economic context as well as on critical changes in its fortunes. These shifting fortunes are crucial to investigate because of the way objects are invested with functions, traditions, symbolic meanings, and memories that are preserved, transformed, or lost when the objects are removed from the cultural contexts and geographic settings in which they were created and change ownership. What story do these rimmonim tell, who owned them, what did they “experience,” and what paths did they “travel” before arriving at the museum in Cincinnati?

There is a long artistic tradition of embellishing the scroll of law with silver ornaments to fulfill the requirement of hiddur mitzvah (enhancement of the religious act). Over the centuries, regionally and temporally different designs for rimmonim have developed. These delightful rimmonim are constructed as a high openwork three-tiered steeple. The two middle tiers each have four bells, which are held in rams’ mouths. The top tier is ornamented with festoons, surmounted by a ring of acanthus leaves and supported by lions mounted on their hind legs with palm fronds underneath. As older photographs and catalogue entries of these objects indicate that there was originally a round medallion at the very top of each finial; these are missing today. Apparently, these medallions were inscribed with the Hebrew names of the objects’ original owners. Records indicate that the inscription was identical with the dedication inscribed on a Torah shield in the Skirball collection (2015.17.147), which reads: “Samuel son of Nathan Arieh HaCohen, Tirzah daughter of Joshua”.

Carl Bitzel, the maker of the rimmonim, was active in Augsburg (southern Germany) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Based on its hallmarks, these rimmonim can be dated to the year 1803 . 1 In addition to profane silver works, the Catholic silversmith Bitzel repeatedly created Jewish ceremonial objects commissioned by Jewish patrons, such as Torah ornaments or Hanukkah lamps. It was by no means uncommon at that time in this region for Jewish patrons to approach Christian silversmiths to supply objects for religious use.2

In 2015, these Torah finials entered the Cincinnati Skirball Museum collection as part of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum Collection that had been transferred from Washington DC. Since at least the early 1960s they had been part of the private Judaica collection of Joseph B. and Olyn Horwitz. The Horwitzes of Cleveland were passionate collectors and acquired Judaica starting in the late 1950s. It is not clear from the records from which further provenance the rimmonim originated. There is thus a long gap in our knowledge of the rimmonim´s manufacture in Augsburg and their first owners, until they reappear in the Horwitz Collection in the 1960s. However, a closer look at the objects themselves – a method that is called “autopsy” in provenance research – may help clarify this interesting question in the future: On the bottom of the rimmonim are engraved and painted numbers. It is possible that these numbers are former inventory numbers of a private Judaica collection or museum. The professionally engraved number, based on its lines, suggests an early 20th century German collection, while the second handwritten number may refer to a later inventory. So far, these numbers are not clearly identified. But I will continue to investigate and hopefully answer this question in the future, so that I can discover more about the “biography” of these interesting objects and their meandering journeys.

1 The Rimmonim have also been dated earlier in the past in Horwitz catalogs, but Susan Braunstein has rightly corrected this incorrect dating. Susan Braunstein: Personal vision, the Jacobo and Asea Furman collection of Jewish ceremonial art: The Jewish Museum, New York, July 2-October 6, 1985, pp. 11-12)